ISSN: 0970-938X (Print) | 0976-1683 (Electronic)

Biomedical Research

An International Journal of Medical Sciences

- Biomedical Research (2014) Volume 25, Issue 4

Diagnostic Ability and Factors Influencing the Accuracy of Endoscopic Ultrasonography-guided Fine-needle Aspiration for Solid Lesions In and Adjacent to the Gastrointestinal Tract.

Changfeng Li2, Mitsuhiro Kida1*, Shuko Tokunaga1, Hiroshi Yamauchi1, Kosuke Okuwaki1, Shiro Miyazawa1, Tomohisa Iwai1 and Hidehiko Kikuchi1

1Department of Gastroenterology, Kitasato University East Hospital, Kanagawa 252-0380, Japan

2Endoscopy Center, China-Japan Union Hospital of Jilin University, Changchun, Jilin 130033, P. R. China

- *Corresponding Author:

- Kida M

Department of Gastroenterology

Kitasato University East Hospital

2-1-1 Asamizodai, Sagamihara

Kanagawa 252-0380, Japan

Accepted date: July 27 2014

Endoscopic ultrasonography-guided fine-needle aspiration (EUS-FNA) has become a safe and accurate diagnostic tool for lesions arising from organs adjacent to the gastrointestinal tract, as well as those arising from the gastrointestinal wall. To improve diagnostic accuracy, devices such as needles with side ports have been developed, but studies evaluating the clinical usefulness of such enhancements remain scant. To explore the factors potentially influencing the diagnostic accuracy of endoscopic ultrasonography-guided fine–needle aspiration (EUS–FNA) for solid masses located in and adjacent to the gastrointestinal tract. Totally 484 consecutive patients who underwent diagnostic EUS-FNA for solid lesions in or adjacent to the gastrointestinal tract from January 2008 to December 2012 were reviewed retrospectively. The overall diagnostic accuracy was 87.0% (442/508). The diagnostic accuracy of combined cytologic/histologic analyses was significantly higher compared with either cytologic or histologic analysis alone. Three and/or more needle passes (p<0.01 compared with less than 3 needle passes; OR=4.01, 95% CI: 2.27-7.07) and larger lesions of >2 cm in diameter (p<0.01 compared with masses <2 cm; odds ratio [OR]=3.20, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.68-6.09) were associated with higher diagnostic accuracy. Gauge size (22- and 25-gauge) and side port (with or without) of needle were independent factors for the overall diagnostic accuracy of EUS-FNA.

Conclusion: Lesions ≥2 cm, combined cytologic- histologic analysis and 3 or more needle passes, irrespective of the needle gauge or a side port of needles, were suggested to improve the diagnostic accuracy of EUS-FNA.

Keywords

Endoscopic ultrasonography-guided fine-needle aspiration, pancreatic mass, subepithelial tumor, abnormal lymph node, diagnostic accuracy

Introduction

Since introduced in 1992, endoscopic ultrasonography- guided fine-needle aspiration (EUS-FNA) has become a safe and accurate diagnostic tool for lesions arising from organs adjacent to the gastrointestinal tract (pancreas, lymph nodes), as well as those arising from the gastrointestinal wall. Generally, the diagnostic accuracy of EUS-FNA ranges from 64% to 100%, with a 0% to 3% incidence of complications [1-5]. To improve diagnostic accuracy, devices such as needles with side ports have been developed, but studies evaluating the clinical usefulness of such enhancements remain scant. Recently, many studies have proposed ways to improve the diagnostic accuracy of EUS-FNA, but most involved small numbers of patients or focused on only specific organs or diseases [2,3,5]. Many endoscopists are now attempting to further enhance the diagnostic yield of EUS-FNA, but it remains uncertain whether specific needle systems should be used with a particular technique selected on the basis of tumor characteristics.

In the present study, we prospectively reviewed the results of EUS-FNA in patents not only with pancreatic solid masses but also with other lesions, such as gastrointestinal subepithelial tumors, abnormal lymph nodes, mediastinal masses, and peripancreatic lesions. Our primary objective was to clarify factors that potentially influence the diagnostic accuracy of EUS-FNA. In addition, a crossover study was performed in a subgroup of 150 patients to compare the tissue-sampling adequacy and the diagnostic yield of 22-gauge and 25-gauge needles in the same patients. In another crossover study of 41 patients, 22-gauge needles with or without a side port were both used for EUS-FNA to evaluate the impact of side ports on the diagnostic accuracy of EUS-FNA.

Materials and Methods

Patients

The retrospective study included the clinical records of 484 consecutive patients who underwent diagnostic EUS-FNA from January 2008 through December 2012. All procedures were performed by four veteran physicians and were supervised by an experienced endoscopist. Written informed consent for participation in this study was obtained from all patients. Data were collected on patient demographics, radiographic findings (including ultrasonography [US], computed tomography [CT], magnetic resonance imaging, and endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography [ERCP]), EUS-FNA procedural factors (e.g., tumor characteristics, needle size, number of needle passes, needle pass route), pathological results, and follow-up.

EUS technique

During the study, EUS-FNA was performed with the use of a curved-linear echoendoscope (GF-UCT240 -AL5 or GF-UCT260; Olympus Medical Systems, Tokyo, Japan). Patients were placed under conscious sedation with intravenous midazolam and pethidine, sometimes in combination with propofol as required. Color Doppler imaging was used to exclude intervening vascular structures and to select a safe vessel-free route for needle passage. Puncture was performed with the use of 22-gauge and 25-gauge needles (EZShot2 NA-220H/230H, Olympus Medical Systems), as well as 19-gauge, 22-gauge, and 25-gauge needles (EchoTip Precore/EchoTip Ultra; Wilson-Cook, Winston-Salem, NC, USA). The type and size of needle were chosen at the discretion of the endoscopist. Both 22-gauge and 25-gauge needles were used in 150 patients to evaluate the effect of needle size on the diagnostic accuracy of EUS-FNA in the same patients. In another subgroup of 41 patients, 22-gauge needles with a side port as well as those without a side port were used to perform EUS-FNA in the same patients and thereby assess whether the presence of a side port affected diagnostic accuracy. In this subgroup, Cook needles (EchoTip Precore/ EchoTip Ultra) were used in 30 patients, and Olympus needles (EZShot2 NA-230H/220H) were used in 11.

During each puncture, the needle was advanced into the lesion under direct EUS visualization. The stylet was removed, negative air pressure was delivered using a 10- or 20-cm syringe to the hub of the needle, and suction was applied as the needle was moved back and forth about 10 to 20 times within the lesion. During all EUS-FNA procedures, tissue samples were confirmed macroscopically. On-site cytotechnological assessment was not performed in any patient. The number of needle passes was determined by macroscopically assessing the samples. The aspirated specimens were first pushed out by air delivered with a syringe and placed into a plastic tube filled with normal saline. If the tissue sample was inadequate on macroscopic inspection, a maximum number of 7 needle passes were additionally performed. Saline containing the aspirated material was transferred to a Petri dish and examined macroscopically. Grayish white, worm-like tissue samples were harvested for histologic examination. The remaining saline was centrifuged, and the sediment was smeared on a plate and examined cytologically.

Diagnostic interpretation

Each aspirated specimen was considered adequate for histological and cytologic examination if it contained a coherent tissue specimen and cells from the target lesion. On the basis of the cytologist’s report, the cytologic specimens were classified as malignancy, suspected malignancy, atypical, or negative for malignancy. A classification of malignancy or suspected malignancy was considered to indicate malignant disease. A classification of atypical or negative for malignancy was interpreted as benign or inflammatory disease. Immunocytochemical and immunohistochemical studies were performed if lesions had a suspected diagnosis of neuroendocrine tumor, leiomyoma, gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST), schwannoma, or lymphoma. The final diagnosis was comprehensively based on cytologic or histologic findings on EUS-FNA (including repeat EUS-FNA), the histologic diagnosis derived from pathological examinations of surgical specimens or other tissue specimens, the results of cytologic examinations on ERCP and percutaneous puncture of the lesion (guided by US or CT), and the results of follow-up radiologic imaging studies. Moreover, all lesions considered benign (e.g., focal pancreatitis, benign lymphadenopathy) had to have negative findings on repeated imaging studies or a clinical course consistent with benign disease (or both) after at least 6 months of follow-up.

Patients in whom a final diagnosis could not be established were excluded. In our study, diagnostic accuracy was defined as concordance between the diagnosis on EUS-FNA and the final diagnosis. Technical success was defined as proper puncture of the target lesion with the acquisition of some visible samples or fragments of tissue by means of EUS-FNA. If the needle was unable to exit from the channel owing to the angulation of the endoscope tip, the procedure was regarded as a technical failure.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using McNemar χ2 test, Fisher’s exact test, and univariate and multivariate logistic regression analysis. p <0.05 was statistical significance. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 19.0 software (SPSS In., Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

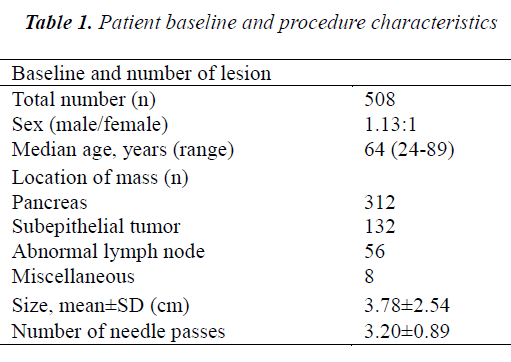

A total of 484 patients who underwent 508 EUS-FNA procedures were studied retrospectively. Fifteen patients were excluded because the final diagnosis could not be confirmed. Patient demographics and lesion characteristics are summarized in Table 1. The average age of the 484 patients was 64.2 years (range: 24-89), and the sex ratio was 1.13:1 (men:women). The mean lesion size was 3.78±2.54 cm (range: 0.8-18 cm). The mean number of needle passes was 3.2±0.89 (range: 1-7) per procedure. Repeat EUS-FNA procedures were conducted in 22 patients (2 times in 20 patients and 3 times in 2 patients). No severe complications of EUS-FNA occurred.

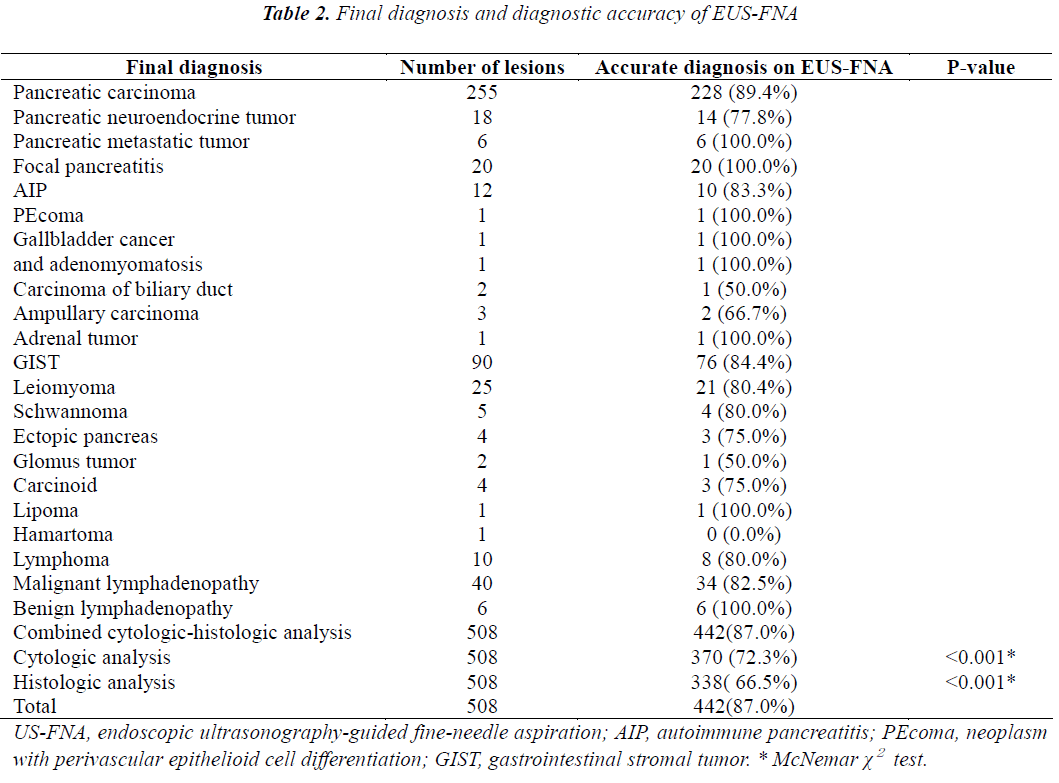

The final diagnoses are shown in Table 2. The overall diagnostic accuracy was 87.0% (442/508). The diagnostic accuracy of combined cytologic-histologic analysis (87%) was significantly superior to that of either cytologic analysis (72.3%) or histologic analysis (64.5%) alone (both p<0.001). The lesions consisted of 312 pancreatic masses, 132 subepithelial tumors, 56 mediastinal or abdominal enlarged lymph nodes, and 8 miscellaneous masses. In the subgroup of patients whom EUS-FNA was performed with both 22- and 25-gauge needles, the mean lesion size was 3.57±1.56 cm (range: 1.0-12 cm). The lesions consisted of 91 pancreatic masses, 36 subepithelial tumors, 21 abnormal lymph nodes, and 2 miscellaneous tumors. In the subgroup of 41 patients whom EUS-FNA procedures were performed using 22-gauge needles with and without a side port, the mean lesion size was 3.63±1.61 cm (range: 1.2-8 cm). The lesions consisted of 24 pancreatic masses, 12 subepithelial tumors, and 5 enlarged lymph nodes.

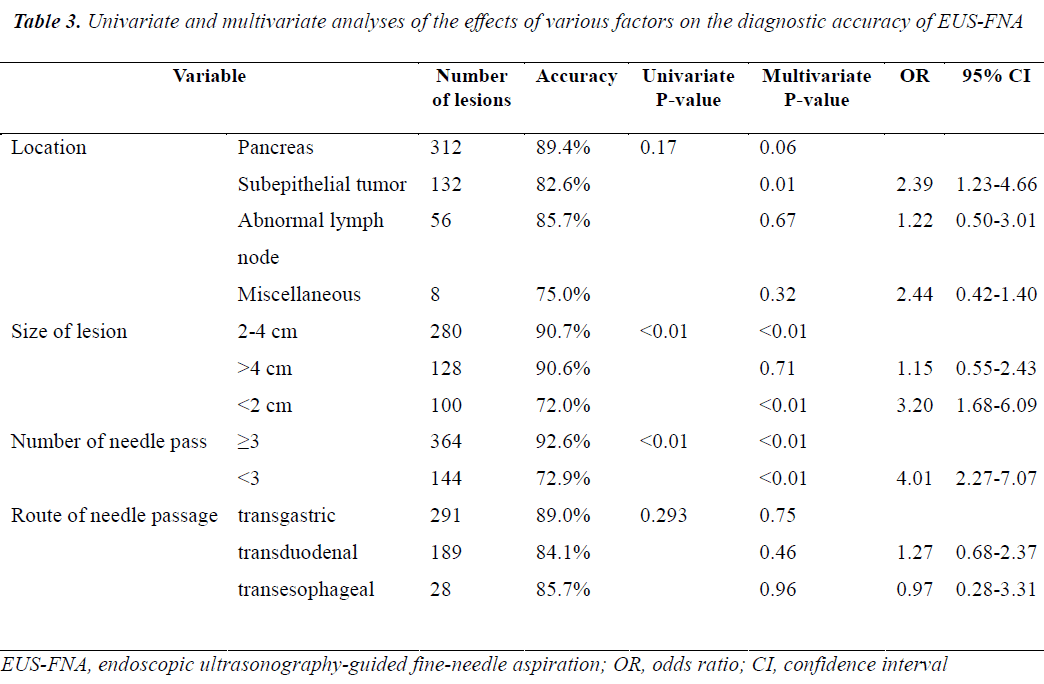

The results of univariate and multivariate analyses performed to identify factors affecting the diagnostic accuracy of EUS-FNA are shown in Table 3. On multivariate analysis, both lesion size and the number of needle passes were found to affect the diagnostic accuracy of EUS-FNA, while mass location and needle passage route were not correlated to the yield of EUS-FNA. The diagnostic accuracy of EUS-FNA was higher for masses 2 to 4 cm in diameter than those <2 cm in diameter (p<0.01; OR=3.20, 95% CI: 1.68-6.09). Diagnostic accuracy did not differ between lesions 2 to 4 cm in diameter and those >4 cm in diameter (p=0.71; OR=1.15, 95% CI: 0.55-2.43). Diagnostic accuracy was higher with 3 or more needle passes than with less than 3 needle passes (p<0.01; OR=4.01, 95% CI: 2.27-7.07). The diagnostic yield was lower for subepithelial tumors than for pancreatic tumors (p<0.05; OR=2.39, 95% CI: 1.23-4.66).

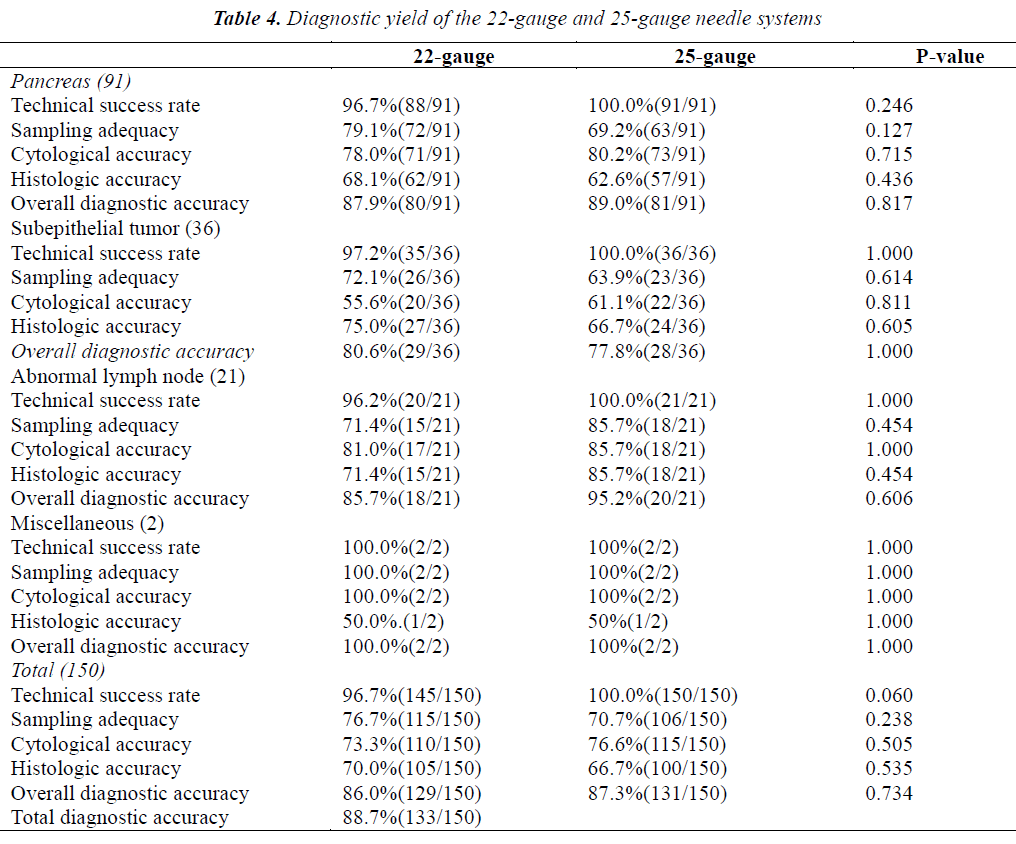

A total of 150 EUS-FNA procedures were carried out using both 22- and 25-gauge needles, and each needle was used 1.0 or 2.0 times. The sequence of the needle was randomly determined. The technical success rate, sampling adequacy, and cytologic and pathologic results are shown according to needle gauge in Table 4. In this subgroup analysis, the total diagnostic accuracy was 88.7% (133/150). The overall diagnostic accuracy of EUS-FNA performed using 22-gauge needles was similar to that of EUS-FNA performed using 25-gauge needles (87.3% vs 86%; p=0.734). The sampling adequacy rate with 22-gauge needles was not significantly higher than that with 25-gauge needles (76.7% vs 70.7%; p=0.238). The technical success rate with 22-gauge needles was similar to that with 25-gauge needles (96.7 vs 100%, p=0.06). Overall, sampling adequacy, cytologic accuracy, and histologic accuracy did not differ significantly between the two sizes of needles. Moreover, the technical success rate, sampling adequacy, cytologic accuracy, and histologic accuracy were similar with 22- and 25-gauges needles not only for pancreatic solid masses, but also for subepithelial tumors and miscellaneous tumors. For abnormal lymph nodes, 25-gauge needles were not significantly superior to 22 gauge in terms of sampling adequacy and histologic accuracy (both 85.7% vs 71.4%; p=0.454).

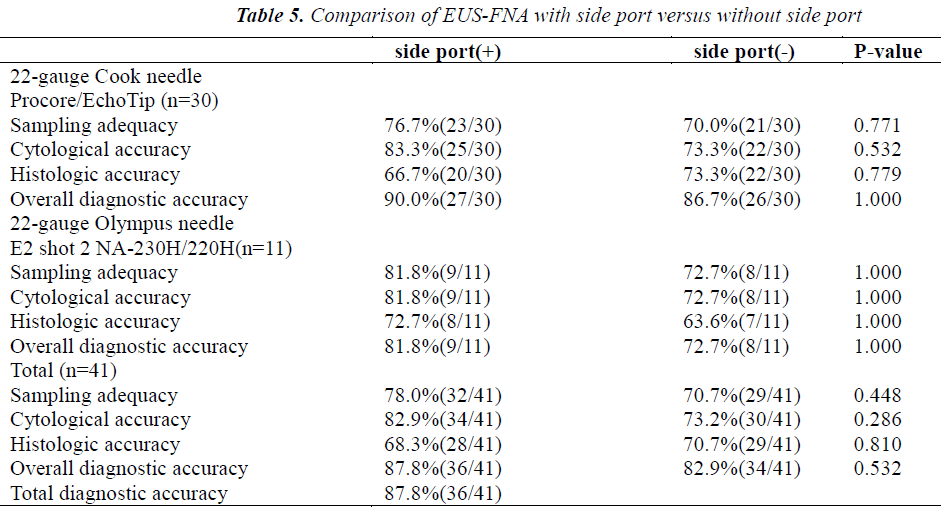

The results of comparing EUS-FNA procedures performed using 22-gauge needles with and without a side port in the same 41 patients are shown in Table 5. The overall diagnostic accuracy was 87.8% (36/41). Needles with a side port had slightly but not significantly higher sampling adequacy (78% vs 70.7%; p=0.448) and cytologic accuracy (82.9% vs 73.2%; p=0.286) than needles without a side port. The overall diagnostic accuracy and histologic accuracy were similar for the 2 types of needles (Table 5). Overall, sampling adequacy, cytologic accuracy, histologic accuracy, and overall diagnostic accuracy did not differ significantly between needles with and those without a side port. Similar results were obtained for both Cook needles and Olympus needles (Table 5).

Discussion

In the present study, the results of 508 EUS-FNA procedures in patients with upper gastrointestinal subepithelial tumors and perigastrointestinal solid lesions were analyzed retrospectively. The final diagnostic accuracy was 87.0%,consistent with the results of previous studies [2-6]. Many variables have been associated with successful and high-yield EUS-FNA. Factors potentially affecting the diagnostic accuracy of EUS-FNA include the endoscopist’s skill [7], lesion size, the number of needle passes, the needle system used (including the effects of needle size and the presence or absence of a side port), whether EUS-FNA is repeated, the use of rapid on-site evaluation (ROSE) [8], and the use of combined cytologic- histologic analysis [9]. The present study attempted to clarify the effects of these factors on diagnostic accuracy. We found that the diagnostic accuracy of EUS-FNA increased significantly when both cytologic analysis and histologic analysis (87.0%) were performed, as compared with either cytologic analysis (72.3%) or histologic analysis (66.5%) alone (both p<0.001). Most previous studies have focused only on cytologic analysis [1,10,11] and distinguishing between malignant and benign lesions. Moreover, the results of cytologic analysis of EUS-FNA samples might be negatively affected by factors such as a limited yield, especially when the aim is to obtain a specific histologic diagnosis. Histologic assessment may be required for better characterization of rare tumors, such as pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors, lymphoma, metastatic tumors, and autoimmune pancreatitis. Cytologic analysis and histologic analysis are complementary diagnostic tools, and we recommend that specimens of solid lesions obtained by EUS-FNA undergo combined cytologic-histologic analysis.

On multivariate analysis, mass location and the needle passage route were unrelated to the diagnostic yield of EUS-FNA. However, the diagnostic yield of gastrointestinal subepithelial tumors was lower than that of pancreatic tumors (82.6 vs 89.4%, P<0.05), which is supported by the results of Sakamoto et al. [12] We speculate that some subepithelial tumors are very mobile and hard, making it difficult to obtain adequate tissue specimens. Moreover, the diagnosis of pancreatic tumors depends mainly on the cytologic examination, which has higher positive results for the pancreas, while the diagnosis of subepithelial tumors depends primarily on pathologic examination, which has relatively low positive results.

In the present study, multivariate analysis showed that the number of needle passes was independently related to the diagnostic accuracy of EUS-FNA. Nonetheless, the effect of the number of needle passes on the diagnostic accuracy of EUS-FNA remains controversial. Nguyen et al.[13] recommended that 6 needle passes should be routinely performed when EUS-FNA of pancreatic masses is done without a cytopathologist in attendance. In previous study [14], a median number of 3.4 passes was necessary for all indications; for lymph nodes, no further increase in yield was obtained beyond 5 passes, whereas the corresponding cutoff value for the pancreas was 7 passes. In contrast, Turner et al.[15] argued that only a small number of needle passes were required to obtain a relatively high diagnostic yield for pancreatic neoplasms, even without on-site cytopathologic evaluation. Study reported no association between a higher yield and an increased number of needle passes for pancreatic masses or gastric subepithelial tumors[16]. In the present study, the mean number of needle passes was 3.2±0.89 (range: 1-7) per procedure, and 3 or more needle passes had a higher diagnostic yield than less than 3 passes (92.6% vs 72.9%, p<0.01). Because we did not have access to rapid on-site assessment, sampling was completed when the endoscopist deemed that adequate tissue had been obtained macroscopically. For difficult-to-sample lesions located in or adjacent to the distal duodenum or small/hard lesions, more than 4 needle passes were needed to obtain sufficient samples. A higher number of needle passes was not associated with any complication in our study. We consequently recommend that 3 or more needle passes are performed to ensure the diagnostic accuracy of EUS-FNA in the absence of on-site cytotechnological evaluation.

Multivariate analysis of the results suggested that the diagnostic accuracy of EUS-FNA is also affected by lesion size. Studies have examined the effects of lesion size on the diagnostic accuracy of EUS-FNA. Ali et al.[17] reported that the diagnostic accuracy of EUS-FNA for solid pancreatic lesions strongly correlates with tumor size. Agarwal et al.[18] similarly showed that the diagnostic accuracy of EUS-FNA was lower for lesions less than 2 cm in diameter than for lesions more than 2 cm in patients with a suspected diagnosis of pancreatic cancer. In contrast, Uehara et al.[19] reported that diagnostic accuracies were equally good for small lesions <1 cm in diameter. Eric et al. [1] suggested that the target-lesion size did not affect the adequacy of the tissue specimen obtained by EUS-FNA. The results of all of these previous studies were derived from smaller study groups than our study. In our series, we classified lesion size into three categories: <2 cm, 2-4 cm, and >4 cm. Our experience indicated that a lesion diameter of <2 cm can cause difficulty in targeting lesions and acquiring adequate samples on back-and-forth movement of the needle. Sahai et al.[20] also showed that the diagnostic accuracy of EUS-FNA was lower when pancreatic lesions measured <2 cm, even when adequate samples were obtained. In our study, the diagnostic yield for lesions 2 to 4 cm in diameter was similar to that of lesions >4 cm in diameter (90.8% vs 90.3%, p=0.71), but the diagnostic accuracy was significantly lower for lesions <2 cm in diameter than for larger lesions (p<0.01), as has been suggested in previous reports [3,18].

Needle size is an important determinant of the diagnostic accuracy of EUS-FNA. At present, FNA needles are available in three gauges: 25, 22, and 19. To enhance the diagnostic accuracy of EUS-FNA, 19-gauge needles and Trucut biopsy needles have been developed. Such needles are generally used when adequate tissue cannot be acquired with 22-gauge needles or when large tissue samples are required for definitive histologic diagnosis, such as in autoimmune pancreatitis, GIST, and malignant lymphoma. However, it is usually difficult to puncture lesions situated at the head of the pancreas, particularly the uncinate process, with 19-gauge or Trucut needles. In addition, large gauge needles have a potentially greater risk of causing complications, particularly perforation, pancreatitis, and bleeding[21]. A general consensus has been reached regarding the advantages and disadvantages of 19-gauge or Trucut needles [10,21-23], and 22-gauge needles are now most widely used worldwide. Problems in cytologic interpretation of EUS-FNA aspirate specimens arise when the material acquired is contaminated by blood or cellular debris[21]. A 22-gauge needle is sometimes unable to penetrate calcified or hard masses. Diagnostic accuracy has been attempted to be improved by the development of smaller diameter 25-gauge needles. Theoretically, a smaller needle might be less traumatic and more easily penetrate not only small, mobile lesions but also calcified or hard masses. This notion was supported by results of Degirmenci et al. [24]. A previous study has reported that a 25-gauge needle can easily puncture lesions located at the head of the pancreas, particularly those at the uncinate process, which are considered difficult to puncture, as well as small subepithelial tumors[22]. This finding is supported by the results of our study.

Five technical failures occurred with 22-gauge needles when the scope was completely angulated in the distal duodenum, but none occurred with 25-gauge needles (96.7% vs 100%, borderline significance, p=0.06). The higher technical success rate of EUS-FNA performed with a 25-gauge needle is attributed to its flexibility due to its thinner caliber as compared with a 22-gauge needle. Several previous studies have compared diagnostic yields between 22- and 25-gauge needles; however, most of these studies [21,23,25] focused on pancreatic lesions, and EUS-FNA procedures were not performed with both 22- and 25-gauge needles in the same patients. Thus, patient- related factors may have affected the results of EUS-FNA despite no statistically significant differences in baseline clinical characteristics. To eliminate patient- dependent variability in our study, a paired comparative analysis was conducted using both 22- and 25-gauge needles in the same 150 patients. The order of needle usage was randomized to minimize order-related effects. Our results showed that overall diagnostic accuracy was similar for 22- and 25-gauge needles, consistent with the findings of previous reports [6,22,25]. In our study, 5 technical failures occurred when the operator attempted to puncture solid lesions from the distal duodenum with a 22-gauge needle. This finding suggests that a 25-gauge needle may be easier to use, even if the tip of the scope is fully angulated.

The sampling adequacy rate was slightly higher with 22-gauge needles than with 25-gauge needles (76.7% vs 70.7%), suggesting that a thicker needle may acquire more tissue and provide a more accurate histologic diagnosis; however, the difference was not statistically significant (p=0.238). On the other hand, it was easier to puncture hard and difficult lesions with a 25-gauge needle. Overall, sampling adequacy, cytologic accuracy, and histologic accuracy did not differ significantly between the use of a 22-gauge needle and a 25-gauge needle. Moreover, the sampling adequacy, cytologic accuracy, and histologic accuracy were similar for 22- and 25-gauge needles not only for pancreatic solid masses but also for subepithelial tumors, consistent with the findings of Rong et al6. However, for abnormal lymph nodes, a 25-gauge needle provided slightly better sampling adequacy and higher histologic yield than a 22-gauge needle (both 85.7% vs 71.4%), but the differences were not statistically significant (both p>0.05). Our findings suggest that calcified or hard lymph nodes might be easier to penetrate with a thinner needle than a thicker needle. Imazu et al. [26] also reported the superior performance of 25-gauge needles for EUS-FNA of lymph nodes. However, for enlarged lymph nodes, our results did not reveal any significant difference in overall diagnostic accuracy or cytologic accuracy between 22- and 25-gauge needles. In our series, the small number of abnormal lymph nodes studied did not allow definite conclusions to be drawn. Further studies are needed to clarify the rationale for the optimal use of EUS-FNA needles according to lesion characteristics.

To increase tissue sampling and decrease the required number of passes during EUS-FNA, needles incorporating a side port have been developed. Kaffes et al.[27] reported that needles with a side port were safe and effective when used for EUS FNA in standard indications, without any complications or device failures in their series. Needles with a side port had a high diagnostic accuracy, often at first pass. Nevertheless, their study had clear limitations. The sample size was too small, and needles with a side port were not compared with conventional needles. In our study, 41 EUS-FNA procedures were performed using 22-gauge needles both with and without a side port. Needles with a side port provided slightly but not significantly higher sampling adequacy (78% vs 70.7%; p=0.448) and cytologic accuracy (82.9% vs 73.2%; p=0.286) than needles without a side port. Despite the same size needle, the side-port appears to increase tissue acquisition as compared with conventional needles. The exact mechanism for this increase is unclear. One explanation is that suction engages twice as much cellular material because there are twice as many holes in the needle tip[27]. The overall diagnostic accuracy and histologic accuracy were similar for needles with and those without a side port. Our results suggest that needles with a side port may be superior to conventional needles with respect to sampling adequacy and cytologic analysis. Indeed, to the best of our knowledge, the present study is the only paired trial to compare needles with a side port with conventional needles. Randomized, multicenter controlled trials of larger number of patients in are needed to confirm our conclusions.

Conclusion

The diagnostic accuracy of EUS-FNA was significantly higher for lesions =2 cm in diameter than for smaller lesions. Combined cytologic-histologic analysis and 3 or more needle passes were suggested to improve the diagnostic accuracy of EUS-FNA in the absence of on-site cytopathological assessment. The 22- and 25-gauge needles were independent factors for the overall diagnostic accuracy of both pancreatic solid lesions and subepithelial tumors. In addition, 25-gauge needles were suggested to provide the identical diagnostic accuracy to 22-gauge needles for EUS-FNA of lymph nodes and lesions in and adjacent to the distal duodenum. The diagnostic yield of EUS-FNA performed with needles with a side port is currently equivalent to that performed with needles without a side port.

References

- Wee E, Lakhtakia S, Gupta R, Sekaran A, Kalapala R, Monga A, et al. Endoscopic ultrasound guided fine-needle aspiration of lymph nodes and solid masses: factors influencing the cellularity and adequacy of the aspirate. J Clin Gastroenterol 2012; 46:487-93.

- Kida M. Pancreatic masses. Gastrointest Endosc 2009; 69 (2 suppl): S102-109.

- Rabindra RW, Kennth F, Binmoceller CM, Shergill AK, Shaw RE, Jaffee IM, et al. Yield and performance characteristics of endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration for diagnosing upper GI tract stromal tumors. Dig Dis Sci 2011; 56: 1757-1762.

- Ramesh J, Varadarajulu S. How can we get the best results with endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration? Clin Endosc 2012; 45: 132-137.

- Nakahara O, Yamao K, Bhatia V, Sawaki A, Mizuno N, Takagi T, et al. Usefulness of endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration for undiagnosed intra-abdominal lymphadenopathy. J Gastroenterol 2009; 44: 562-567.

- Rong L, Kida M, Yamauchi H, Okuwaki K, Miyazawa S, Iwai T, et al. Factors affecting the diagnostic accuracy of endoscopic ultrasonography-guided fine-needle aspiration (EUS-FNA) for upper gastrointestinal submucosal or extraluminal solid mass lesions. Dig Endosc 2012; 24: 358-363.

- Savides TJ, Donohue M, Hunt G, Al-Haddad M, Aslanian H, Ben-Menachem T, et al. EUS-guided FNA diagnostic yield of malignancy in solid pancreatic masses: a benchmark for quality performance measurement. Gastrointest Endosc 2007; 66: 277-282.

- Polkowski M, Larghi A, Weynand B, Boustière C, Giovannini M, Pujol B, et al. Learning, techniques, and complications of endoscopic ultrasound (EUS)-guided sampling in gastroenterology: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Technical Guideline. Endoscopy 2012; 44: 190-206.

- Möller K, Papanikolaou IS, Toermer T, Delicha EM, Sarbia M, Schenck U, et al. EUS-guided FNA of solid pancreatic masses: high yield of 2 passes with combined histologic-cytologic analysis. Gastrointest Endosc 2009; 70: 60-69.

- Uehara H, Ikezawa K, Kawada N, Fukutake N, Katayama K, Takakura R, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration for suspected pancreatic malignancy in relation to the size of lesions. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2011; 26: 1256-1261.

- Iglesias-Garcia J, Dominguez-Munoz JE, Abdulkader I, Larino-Noia J, Eugenyeva E, Lozano-Leon A, et al. Influence of on-site cytopathology evaluation on the diagnostic accuracy of endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration (EUS-FNA) of solid pancreatic masses. Am J Gastroenterol 2011; 106: 1705-1710.

- Sakamoto H, Kitano M, Kudo M. Diagnosis of subepithelial tumors in the upper gastrointestinal tract by endoscopic ultrasonography. World J Radiol 2010; 28: 289-297.

- Nguyen YP, Maple JT, Zhang Q, Ylagan LR, Zhai J, Kohlmeier C, et al. Reliability of gross visual assessment of specimen adequacy during EUS-guided FNA of pancreatic masses. Gastrointest Endosc 2009; 69: 1264-1270.

- LeBlanc JK, Ciaccia D, Al-Assi MT, McGrath K, Imperiale T, Tao LC, et al. Optimal number of EUS-guided fine needle passes to obtain a correct diagnosis. Gastrointest Endosc 2004; 59: 475-81.

- Turner BG, Cizginer S, Agarwal D, Yang J, Pitman MB, Brugge WR. Diagnosis of pancreatic neoplasia with EUS and FNA: a report of accuracy. Gastrointest Endosc 2010; 71: 91-98.

- Mekky MA, Yamao K, Sawaki A, Mizuno N, Hara K, Nafeh MA, et al. Diagnostic utility of EUS-guided FNA in patients with gastric submucosal tumors. Gastrointest Endosc 2010; 71: 913-919.

- Siddiqui AA, Brown LJ, Hong AK, Draganova- Tacheva RA, Korenblit J, Loren DE, et al. Relationship of pancreatic mass size and diagnostic yield of endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration. Dig Dis Sci 2011; 56: 3370-3375.

- Agarwal B, Abu-Hamda E, Molke KL, Correa AM, Ho L. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration and multi-detector spiral CT in the diagnosis of pancreatic cancer. Am J Gastroenterol 2004; 99: 844-850.

- Uehara H, Ikezawa K, Kawada N, Fukutake N, Katayama K, Takakura R, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration for suspected pancreatic malignancy in relation to the size of lesions. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2011; 26:1256-1261.

- Sahai AV, Schembre D, Stevens PD, Chak A, Isenberg G, Lightdale CJ, et al. A multicenter U.S. experience with EUS-guided fine-needle aspiration using the Olympus GF-UM30P echoendoscope: safety and effectiveness. Gastrointest Endosc 1999; 50: 792-796.

- Yusuf TE, Ho S, Pavey DA, Michael H, Gress FG. Retrospective analysis of the utility of endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration (EUS-FNA) in pancreatic masses, using a 22-gauge or 25-gauge needle system: a multicenter experience. Endoscopy 2009; 41:445-448.

- Kida M, Araki M, Miyazawa S, Ikeda H, Takezawa M, Kikuchi H, et al. Comparison of diagnostic accuracy of endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration with 22- and 25-gauge needles in the same patients. J Interv Gastroenterol 2011; 1: 102-107.

- Sakamoto H, Kitano M, Komaki T, Noda K, Chikugo T, Dote K, et al. Prospective comparative study of the EUS guided 25-gauge FNA needle with the 19-gauge Trucut needle and 22-gauge FNA needle in patients with solid pancreatic masses. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2009; 24: 384-90.

- Degirmenci B, Haktanir A, Albayrak R, Acar M, Sahin DA, Sahin O, et al. Sonographically guided fine-needle biopsy of thyroid nodules: the effects of nodule characteristics, sampling technique, and needle size on the adequacy of cytological material. Clin Radiol 2007; 62:798-803.

- Lee JH, Stewart J, Ross WA, Anandasabapathy S, Xiao L, Staerkel G. Blinded prospective comparison of performance of 22-gauge and 25-gauge needles in endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration of pancreas and peri-pancreatic lesions. Dig Dis Sci 2009; 54: 2274-2281.

- Imazu H, Uchiyama Y, Kakutani H, Ikeda K, Sumiyama K, Kaise M, et al. A prospective comparison of EUS-guided FNA using 25-gauge and 22-gauge needles. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2009; 2009: 546390.

- Kaffes A, Corte C. Fine needle aspiration at endoscopic ultrasound with a novel side-port needle: a pilot experience. Therap Adv Gastroenterol 2012; 5: 89-94.