ISSN: 0970-938X (Print) | 0976-1683 (Electronic)

Biomedical Research

An International Journal of Medical Sciences

Research Article - Biomedical Research (2017) Volume 28, Issue 15

Laparoscopic versus open appendectomy on serum levels of cytokines in children with perforated appendices, peritonitis and sepsis

1Department of General Surgery, Children’s Hospital of Wuhan, No.100 Xianggang Road, Wuhan, Hubei, PR China

2Department of General Surgery, Children’s Hospital of Shanghai, No. 355 Luding Road, Putuo District, Shanghai, PR China

3Department of Gastroenterology, Children’s Hospital of Wuhan, No.100 Xianggang Road, Wuhan, Hubei, PR China

#These authors have equally contributed for this work

- *Corresponding Author:

- Zhou Shiqiong

Department of Gastroenterology

Children’s Hospital of Wuhan

Wuhan, Hubei, PR China

Accepted date: June 29, 2017

Purpose: To examine the effect of Laparoscopic (LA) and Open Appendectomy (OA) on serum levels of inflammatory factors Interleukin-6 (IL-6) and Tumor Necrosis Factor-α (TNF-α) and anti-inflammatory factor, Interleukin-10 (IL-10), in children with perforated appendices, peritonitis and sepsis.

Methods: 36 children received LA and 31 children received OA were included. Serum IL-6, TNF-α and IL-10 were determined at different time points before and after surgery with double-antibody sandwich ELISA.

Results: Preoperative serum IL-6, TNF-α and IL-10 were not significantly different between LA group and OA group (P>0.05). However, serum IL-6 and TNF-α in LA group were significantly lower than those in OA group on postoperative days 1, 3 and 7 (all P<0.05). Serum IL-10 in LA group was initially higher than that in OA group on postoperative days 1 and 3 (P<0.05), but became significantly lower than that in OA group on postoperative day 7 (P<0.05).

Conclusion: Decreased inflammatory response and enhanced anti-inflammatory response were evident postoperatively in children received LA reflected by reduced serum IL-6 and TNF-α, and increased serum IL-10, suggesting LA is a better choice over OA.

Keywords

Perforated appendix, Laparoscopic appendectomy, Open appendectomy, Inflammatory factor, Children.

List of Abbreviations

LA: Laprascopic; OA: Open appendectomy; IL-6: Interleukin-6; TNF-α: Tumor necrosis factor-α; IL-10: Interleukin-10; ELISA: Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay.

Introduction

With technical advancements, clinical application of laparoscopic technique has become increasingly broadened for treating various infectious abdominal diseases including acute cholecystitis, acute appendicitis, gastrointestinal tract perforation and so on [1-4]. However, whether laparoscopy and carbon dioxide pneumoperitoneum (CO2PP) can be used in treating peritonitis remains controversial.

A major concern is that increased intra-abdominal pressure during laparoscopic surgery may increase risks of bacteraemia that can lead to systemic inflammatory response. Studies on the effect of pneumoperitoneum on systemic inflammation during sepsis remain contradictory [5,6]. Some studies reported that CO2PP is associated with positive-end expiratory pressure and has no impact on systemic expansion of intra-abdominal Escherichia coli infection, but other studies showed that CO2PP can influence septic development by increasing bacterial (E. coli) translocation in rats [7,8]. More recent studies have shown that CO2PP can alleviate peritonitis and systemic inflammatory response in experimental models of E. coli-peritonitis and sepsis, and extracellular acidic pH environments after CO2 insufflation during laparoscopic surgery can promote macrophage activation and function [9,10]. Perforated appendix is one of the common causes for acute abdominal diseases in children and is usually accompanied by severe peritonitis and septicopyemia. So far, only early effects of pneumoperitoneum during peritonitis have been assessed, and the comparison between conventional and laparoscopic surgery has been only conducted in animal models which is not yet in human patients [11,12].

In current study, we aimed to compare the effect of laparoscope and conventional open appendectomy on postoperative infection to explore a better clinical approach.

Subjects and Methods

Subjects

67 children admitted to the Surgery Department of the Children’s Hospital of Wuhan and surgically diagnosed with perforated appendices and peritonitis accompanied with sepsis were enrolled in this study.

Diagnoses were further confirmed by pathological examination. 36 children including 15 females and 21 males (2.8-14 y old and 15-42 kg) were included in LA group. 31 children including 12 females and 19 males (2.5-16 y old and 13-48 kg) were included in OA group.

Children were randomly grouped based on option of respective guardians. Operations were executed by same surgical team and in the same premises. No subjects had any recent history of infection or chronic disease. Subjects with immune diseases were excluded.

No statistical differences were noted between the two groups with respect to gender, age, weight, time of symptom onset, anesthesia, operative time or time of anesthesia (Χ2=1.251,1.637; Z=0.396~1.782; all P>0.05).

All manipulations were approved by the Ethic Committee of the Children’s Hospital of Wuhan. All patients were well informed and signed written consents.

Methods

Sample collection: Two hours before and 1, 3 and 7 d after operation, 2 ml venous blood was drawn from each subject. The samples were centrifuged at 5000 rpm for 10 min. Serum was collected and stored at -20°C until use.

Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA): Doubleantibody sandwich ELISA was used to determine serum levels of IL-6, TNF-α and IL-10. ELISA kits were purchased from Shenzhen Dakewe Biotech Co., Ltd. (Shenzhen, China). All procedures were conducted following manufacturer’s instructions.

Statistics

SPSS 17.0 software was used for data analysis. Data were shown as mean ± standard deviation (x ± s).

Comparison between two groups was made by t-test or rank sum test. Enumeration data were analyzed using X2 test. Significance was accepted if P<0.05.

Results

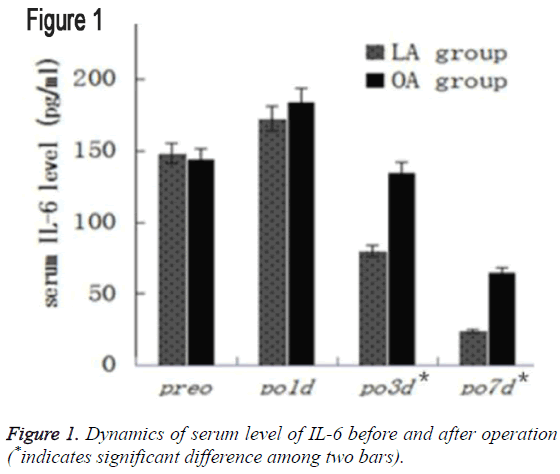

Dynamics of serum IL-6 before and after operation

Preoperative serum IL-6 in the two groups was comparable (P>0.05). Serum IL-6 significantly increased on postoperative day 1 in both groups (P<0.05), but gradually declined thereafter.

On postoperative day 3, IL-6 level in the LA group had significantly decreased compared to postoperative day 1 and even its preoperative level (P<0.05). Such a rapid decrement was not observed in the OA group (P>0.05).

On all three postoperative time points, IL-6 level in the LA group remained significantly lower than that in the OA group (P<0.05), as shown in Table 1 and Figure 1.

| Group | Pre-operative | Post-operative 1 d | Post-operative 3 d | Post-operative 7 d |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LA | 148.3 ± 19.0 | 172.7 ± 23.2a* | 80.1 ± 11.3b* | 23.9 ± 4.9c* |

| OA | 144.2 ± 22.1 | 184.5 ± 26.8a* | 135.3 ± 19.2b | 65.2 ± 16.4c* |

| t | 0.82 | 2.321 | 14.556 | 14.404 |

| p | 0.415 | 0.023* | 0.000* | 0.000* |

Table 1: Dynamics of serum level of IL-6 before and after operation (x ± s, pg/ml).

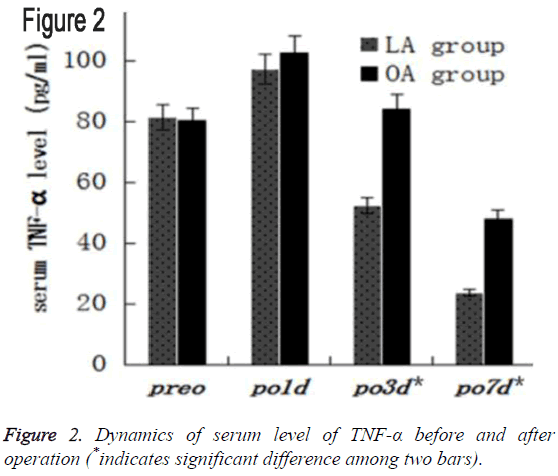

Dynamics of serum TNF-α before and after operation

There was no statistical difference in preoperative serum TNF- α between LA and OA groups (P>0.05). After operation, serum TNF-α were first significantly increased compared to that preoperatively (both P<0.05), and then declined in both groups.

On postoperative day 3, TNF-α in the LA group was significantly decreased than postoperative day 1 (P<0.05), whereas no statistical difference was observed in the OA group (P>0.05).

Moreover, serum TNF-α in the LA group remained significantly lower than that in the OA group on postoperative days 1, 3 and 7 (all P<0.05), as shown in Table 2 and Figure 2.

| Group | Pre-operative | Post-operative 1 d | Post-operative 3 d | Post-operative 7 d |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LA | 81.4 ± 10.7 | 97.3 ± 12.7a* | 52.4 ± 9.3b* | 23.7 ± 6.8c* |

| OA | 80.5 ± 8.9 | 102.8 ± 11.4a* | 84.5 ± 11.7b | 48.3 ± 9.5c* |

| t | 0.405 | 2.41 | 16.678 | 17.152 |

| P | 0.687 | 0.019* | 0.000* | 0.000* |

Table 2: Dynamics of serum level of TNF-α before and after operation (x ± s, pg/ml).

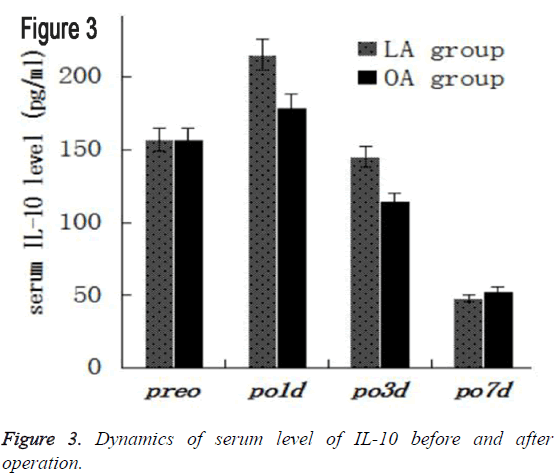

Dynamics of serum IL-10 before and after operation

The preoperative serum IL-10 were comparable between LA and OA groups (P>0.05). After operation, serum IL-10 increased in both groups.

On postoperative days 1, 3 and 7, serum level of IL-10 in the LA group remained significantly higher than that the OA group (P<0.05).

On postoperative day 7, serum level of IL-10 decreased rapidly (P<0.05), but it remained in the OA group, as shown in Table 3 and Figure 3.

| Group | Pre-operative | Post-operative 1 d | Post-operative 3 d | Post-operative 7 d |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LA | 156.9 ± 39.5 | 215.3 ± 57.9a* | 145.3 ± 32.6b* | 47.8 ± 8.4c* |

| OA | 156.8 ± 42.3 | 179.1 ± 48.9a* | 114.4 ± 26.7b* | 52.7 ± 12.3c* |

| t | 0.008 | 7.981 | 7.344 | 1.907 |

| p | 0.994 | 0.000* | 0.000* | 0.061 |

Table 3: Dynamics of serum level of IL-10 before and after operation (x ± s, pg/ml).

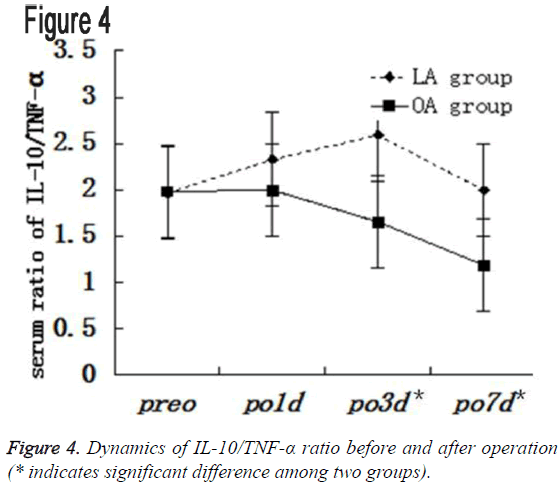

Dynamics of IL-10/TNF-α ratio

There was no statistical difference IL-10/TNF-α ratio before operation between the two groups (P>0.05).

IL-10/TNF-α ratio in the LA group constantly remained higher than that in the OA group on postoperative days 1, 3, and 7 (all P<0.05), as shown in Table 4 and Figure 4.

| Group | Pre-operative | Post-operative 1 d | Post-operative 3 d | Post-operative 7 d |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LA | 1.96 ± 0.32 | 2.33 ± 0.54a* | 2.59 ± 0.59b* | 1.99 ± 0.65c |

| OA | 1.98 ± 0.38 | 1.99 ± 0.41a | 1.65 ± 0.43b | 1.18 ± 0.44c* |

| t | 0.247 | 2.823 | 7.322 | 5.889 |

| p | 0.805 | 0.006* | 0.000* | 0.000* |

Table 4: Dynamics of IL-10/TNF-α ratio before and after operation.

Discussion

In the current study, we found inflammatory response were lower and anti-inflammatory response was higher in postoperative children received LA reflected by reduced serum IL-6 and TNF-α, and increased serum IL-10, suggesting LA is a better choice over OA.

IL-6 indicates early tissue injury and its increments is proportional to surgical trauma and accompanying damage, therefore, it has been proven to be a major index in evaluating the severity of traumatic stress reactions and serves as marker for traumatic prognosis [13]. In present, we found IL-6 were greatly increased after operation and significantly lower in the LA group than in the OA group postoperatively (all P<0.05), indicating children received LA developed had less postoperative stress and immune reactions, which are consistent with studies in mice and women [14,15]. The possible mechanism whereby CO2PP reduces serum IL-6 has been suggested as: 1. Curbing and killing bacteria and inhibiting the growth of Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus; 2. Inducing peritoneum cell acidification, thereby suppressing release of multiple inflammatory mediators and cytokines by macrophages; 3. Inhibiting release of superoxide anion by macrophages and mitochondrial function, thereby alleviating inflammatory reactions [16,17].

On the other hand, serum IL-6 in LA group increased more slowly but declined more rapidly. IL-6 in the LA group began to decline 3 d postoperatively and was significantly lower compared with its pre-operative level. IL-6 in OA group 7 d after operation differed significantly from pre-operative level (P<0.05), indicating that both LA and OA can lead to postoperative stress reactions in affected children, whereas the stress reactions provoked by LA are milder and recovered more rapidly than OA, which may underlie shorter hospital stay of patients received LA [18].

TNF-α is a key pro-inflammatory cytokine after inflammatory stimulation that can activate cytokine cascade reactions during inflammation and directly reflects the severity of an inflammatory response [19]. Early detection of TNF-α is of great significance for evaluating the severity of serious abdominal inflammation [20]. In this study, no statistical significance was observed in serum TNF-α between the two groups before surgery. However, serum TNF-α in LA group were significantly lower on postoperative days 1, 3, and 7 than that in OA group. Moreover, serum TNF-α in LA group increased more slowly but decreased more rapidly than that in OA group. Alleviation of inflammatory response under LA may be also due to CO2PP as reported in rat [21,22].

IL-10 is a key anti-inflammatory cytokine produced by Th2 cells that can inhibit the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-6 and TNF-α [23], thereby preventing deterioration of sepsis and alleviating the damage to distal viscera via which CO2PP may enhance anti-inflammatory cytokine’s releasing and alleviates inflammatory reactions as suggested [24]. Furthermore, IL-10 mainly alleviates hepatic inflammatory injury, delays liver regeneration and reduces TNF-α by decreasing formation of collagen and collagenase. A moderate release of inflammatory mediators in patients with sepsis may contribute to inhibition of inflammatory responses and enhance resistance against inflammation [25]. As an anti-inflammatory factor, IL-10 not only inhibits releasing of proinflammatory cytokines, but also limits injuries resulted from excessive inflammatory responses mediated by pro-inflammatory cytokines. However, a prolonged increase in IL-10 may suppress immune responses and aggravate the severity of disease. Therefore, IL-10/TNF-α ratio should be maintained within proper level from 1.3-1.9 in order to have an antiinflammatory effect [26,27]. Our results revealed that IL-10/ TNF-α ratio in LA group ranged from 1.99-2.59 on postoperative days 1, 3 and 7, and is significantly higher than that in OA group (1.2~1.99), suggesting children received LA had stronger anti-inflammatory potential at all-time points after operation. In the OA group, IL-10/TNF-α ratio on postoperative day 3 was normal and on postoperative day 7 it fell below the normal threshold, indicating that children received OA had less anti-inflammatory potential. These results demonstrated CO2PP contributes to physical clearance of bacteria and toxins and provides protection of normal immune function, which are consistent with previous study [28-30].

Conclusion

LA reduces inflammatory responses in children with perforated appendices, peritonitis and sepsis and enhances the antiinflammatory responses. This study provides evidence of advantages of LA to OA in treating perforated appendices. However, such effects resulted from CO2PP and within LA group, the effect of pressure, gas flow amount, operative time and anesthesia time on postoperative inflammatory responses and even long-term prognosis remains to be studied in future [31].

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All manipulations were approved by the Ethic Committee of the Children’s Hospital of Wuhan. All patients were well informed and signed written consents.

Consent to publish

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

All information supporting the conclusions of this manuscript is included within the article. Any additional information can be obtained upon request.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Funding

None.

Authors Contribution

CSF, YGB, YJ and YXQ carried out the clinical, participated in clinical analysis. DXF, YXQ, BHQ and YJ performed statistical analysis and ELISA. YGG, XQ and ZSQ participated in experimental studies and analyzed data. DXF drafted the paper with inputs from BHQ, ZSQ and YGG. DXF, ZSQ and YGG conceived of the study, and participated in its design and coordination. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgement

Thank MH for the generous help.

Conflict of Interest

None.

References

- Sista F, Schietroma M, Santis GD, Mattei A,Cecilia EM,Piccione F, Leardi S, Carlei F, Amicucci G. Systemic inflammation and immune response after laparotomy vs laparoscopy in patients with acute cholecystitis, complicated by peritonitis. World J Gastrointest Surg 2013; 5: 73-82.

- Chang HK, Han SJ, Choi SH, Oh JT. Feasibility of a laparoscopic approach for generalized peritonitis from perforated appendicitis in children. Yonsei Med J 2013; 54: 1478-1483.

- Katkhouda N, Mavor E, Mason RJ, Campos GM,Soroushyari A,Berne TV. Laparoscopic repair of perforated duodenal ulcers: outcome and efficacy in 30 consecutive patients. Arch Surg J Surg Res 2012; 173: 127-134.

- Chatzimavroudis G, Pavlidis TE, Koutelidakis I, Giamarrelos-Bourboulis EJ,Atmatzidis S,Kontopoulou K. CO2 pneumoperitoneum prolongs survival in an animal model of peritonitis compared to laparotomy. J Surg Res 2009; 152: 69-75.

- Gurtner GC, Robertson CS, Chung SC, Ling TK, Ip SM, Li AK. Effect of carbon dioxide pneumoperitoneum on bacteraemia and endotoxaemia in an animal model of peritonitis. Br J Surg 1995; 82: 844-848.

- Barbaros U, Ozarmagan S, Erbil Y, Bozbora A,Cakar N,Eraksoy H, Kapran Y, Kiran B. Effects of pneumoperitoneum created through CO2 insufflation and parameters of mechanical ventilation (PEEP application) on systemic dissemination of intra-abdominal infections. Surg Endosc 2004; 8: 501-507.

- Horattas MC, Haller N, Ricchiuti D. Increased transperitoneal bacterial translocation in laparoscopic surgery. Surg Endosc 2003; 17: 1464-1467.

- Uzunköy A1, Ozardali I, Celik H, Demirci M. The effect of carbon dioxide pneumoperitoneum on the severity of peritonitis. Ulus Travma Acil Cerrahi Derg 2012; 18: 99-104.

- Grabowski J, Vazquez DE, Costantini T, Cauvi DM,Charles W,Bickler S,Talamini MA, Vega VL, Coimbra R, De Maio A. Tumor necrosis factor expression is ameliorated after exposure to an acidic environment. J Surg Res 2012; 173: 127-134.

- Clary EM, Bruch SM, Lau CL, Ali A,Chekan EG,Garcia-Oria MJ, Eubanks S. Effects of pneumoperitoneum on hemodynamic and systemic immunologic responses to peritonitis in pigs. J Surg Res 2002; 108: 32-38.

- Jacobi CA, Ordemann J, Zieren HU, Volk HD,Bauhofer A,Halle E, Müller JM. Increased systemic inflammation after laparotomy vs laparoscopy in an animal model of peritonitis. Arch Surg 1998; 133: 258-262.

- Cuschieri J, Bulger E, Schaeffer V, Nathens AB,Hennessy L,Minei J, Minei J, Moore EE, O'Keefe G, Sperry J, Remick D, Tompkins R, Maier RV. Early elevation in random plasma IL-6 after severe injury is associated with development of organ failure. Shock 2010; 34: 346-351.

- Luk JM, Tung PH, Wong KF, Chan KL,Law S,Wong J. Laparoscopic surgery induced interleukin-6 levels in serum and gut mucosa: implications of peritoneum integrity and gas factors. Surg Endosc 2009; 23: 370-376.

- Zhang JP, Lu D, Wang W. The comparison between the effects of gynecologic laparoscopy and laparotomy on the body stress reaction. Chin J Pract Gynecol Obstet 2000; 16: 615-616.

- Qin CH, Zhang XL, He HJ. Effect of carbon dioxide pneumoperitoneum on the expression of proinflammatory cytokines and histopathological changes of the pancreas in SD rats with severe acute pancreatitis. Chin H Min Inv Surg 2010; 10: 273-277.

- Wang H, Xu DF, Liu YB. Experimental study for effects of carbon dioxide pneumoperitoneum on the function of macrophage under inflammation. J Laparos Surg 2010; 15: 271-274.

- Masoomi H, Mills S, Dolich MO, Ketana N,Carmichael JC,Nguyen NT, Stamos MJ. Comparison of outcomes of laparoscopic versus open appendectomy in children: data from the Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS), 2006-2008. World J Surg 2012; 36: 573-578.

- Zhang XB, Wang K, Li DS. O2 pneumoperitoneum play an important role in TNF-α and IL-6 in severe abdominal cavity inflammation rats. Acta Acad Med Jiangxi 2009; 49: 11-14.

- Wang H, Xu DF. Research progress of applying laparoscopic surgery using carbon dioxide pneumoperitoneum in treatment of infectious surgical diseases. J Laparos Surg 2010; 15: 151-153.

- Montalto AS, Bitto A, Irrera N, Polito F,Rinaldi M,Antonuccio P, Impellizzeri P, Altavilla D, Squadrito F, Romeo C. CO2PP impact on early liver and lung cytokine expression in a rat model of abdominal sepsis. Surg Endosc 2012; 26: 984-989.

- Hanly EJ, Fuentes JM, Aurora AR, Bachman SL,De Maio A,Marohn MR. Carbon dioxide pneumoperitoneum prevents mortality from sepsis. Surg Endosc 2006; 20: 1482-1487.

- Han T, Li X, Cai D, Zhong Y,Chen L,Geng S, Yin S. Effect of glutamine on apoptosis of intestinal epithelial cells of severe acute pancreatitis rats receiving nutritional support in different ways. Int J Clin Exp Pathol 2013; 6: 503-509.

- Hanly EJ, Aurora AA, Shih SP,Fuentes JM,Marohn MR,De Maio A, Talamini MA. Peritoneal acidosis mediates immune protection in laparoscopic surgery. Surg 2007; 42: 357-364.

- Huang JB, Zhang XP, Lu HY. The role of IL-6, IL-10 and TNF-α in liver damage in children with sepsis. J Clin Pediatr 2012; 30: 15-17.

- Qiao HM, Pang HX, Zhang YF. Changes of IL-6, IL-10 and TNF-α in children with mycoplasma pneumonia. J Clin Pediatr 2012; 30: 59-61.

- Goncalves RM, Scopel KK, Bastos MS,Ferreira MU. Cytokine balance in human malaria: does Plasmodium vivax elicit more inflammatory responses than Plasmodium falciparum? PLoS One 2012; 7: 44394.

- Wang G, Guo ZY, Wu RD. Effect of carbon dioxide pneumoperitoneum on the intra-abdominal infection: An animal study. Chin J Pediatr Surg 2006; 27: 30-33.

- Grabowski JE, Vega VL, Talamini MA, De Maio A. Acidification enhances peritoneal macrophage phagocytic activity. J Surg Res 2008; 147: 206-211.

- Chatzimavroudis G, Pavlidis TE, Koutelidakis I, Giamarrelos-Bourboulis EJ,Atmatzidis S,Kontopoulou K, Marakis G, Atmatzidis K. CO2PP prolongs survival in an animal model of peritonitis compared to laparotomy. J Surg Res 2009; 152: 69-75.

- Du J, Yu PW. Effect of different CO2PP on IL-1β and IL-6 in abdominal cavity. Chin J Gastrointest Surg 2012; 15: 834-836.

- Schietroma M, Carlei F, Cecilia EM, Piccione F,Sista F,De Vita F,De Vita F, Amicucci G. A prospective randomized study of systemic inflammation and immune response after laparoscopic nissen fundoplication performed with standard and low-pressure pneumoperitoneum. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech 2013; 23: 189-196.